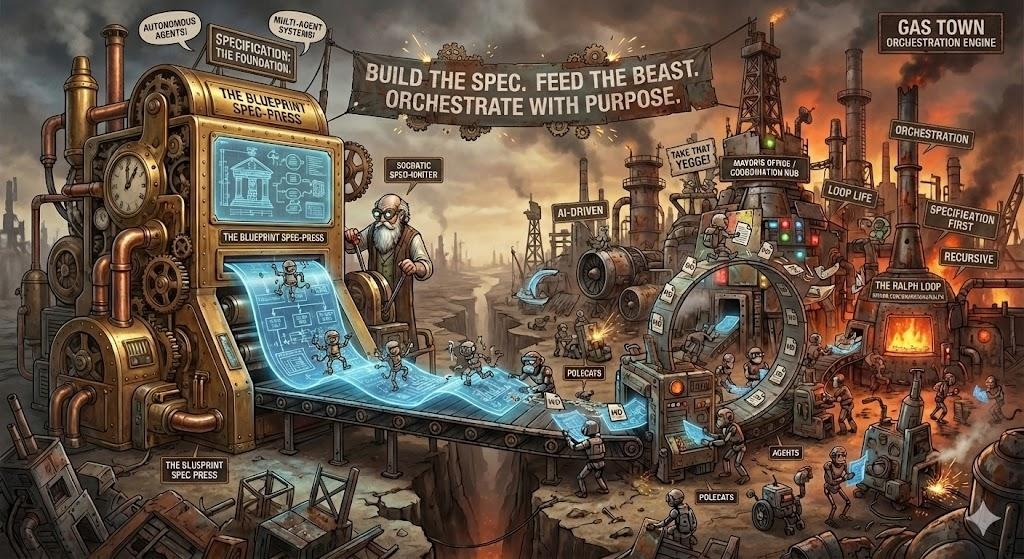

The Factory Without a Design Department

Cursor ran production experiments with hundreds of concurrent agents over weeks. Their initial architecture used flat coordination: equal-status agents with shared-file locking. Twenty agents produced the effective throughput of two or three.

Meanwhile, a developer using Geoffrey Huntley’s “Ralph” technique shipped a $50K contract for $297 in compute costs. The architecture is a bash loop. One agent. One task per iteration. State persisted to a markdown file between iterations. (The $297 reflects API spend only. Specification work, debugging, and review are not included.)

Same underlying models. Radically different results. Cursor built a complex factory floor and it failed. Huntley built a simple one and invested in blueprints instead.

The missing department

The industry is building factories. Cursor, Devin, Claude Code, CrewAI, LangGraph, AutoGen. All orchestration engines. Gartner reported a 1,445% surge in multi-agent system inquiries from Q1 2024 to Q2 2025. Two-thirds of enterprise AI implementations now use multi-agent architectures.

The same industry reports high failure rates for production multi-agent systems. The majority of failures originate from specification and coordination issues rather than technical implementation.

We built the factory. We forgot the design department.

Huntley’s pattern makes this explicit. His workflow has three phases: requirements (specs/*.md), planning (IMPLEMENTATION_PLAN.md), and building (the loop). The blueprints are where the work happens. “LLMs are mirrors of operator skill,” he writes. The results come from investing in specifications, not from sophisticated orchestration.

The blueprint printing press

Scott Logic observed that AI coding assistants have exposed an uncomfortable truth: “many people struggle to articulate what they actually want to build.” We spent decades optimizing for implementation speed while specification skills atrophied. Now implementation is cheap, and specification is the constraint.

The obvious response would be to build tools that help write blueprints. But look at the landscape:

- Cursor: factory

- Devin: factory

- Claude Code: factory

- CrewAI: factory framework

- LangGraph: factory framework

Where is the design department? The blueprint printing press?

The Agentic Handbook documents why agents fail: scope creep, ambiguity, missing deterministic checks. These are blueprint failures, not factory failures. The handbook’s solution is better human discipline. But discipline does not scale. Tooling does.

Why this is hard to build

Blueprints are harder than factories because specs require understanding intent, not just code. The codebase contains what was built. It does not contain why, or what was considered and rejected, or what “good” means in this context.

There is also an infinite regress problem. To build a blueprint-writing agent, you need a blueprint for the blueprint-writer. Turtles all the way down.

But maybe it bottoms out. The AI does not write the blueprint. It interrogates until the human has drawn a good one.

The Socratic design department:

- Human provides raw intent: “I want users to track usage metrics”

- AI decomposes: “What counts as a metric? What’s the retention policy? Who can see what?”

- AI applies the scope test: “Can you describe this in one sentence without ‘and’?”

- AI challenges edge cases: “What happens when the service is down? What’s explicitly out of scope?”

- AI validates: “Here’s what I understood. Here are the ambiguities I still see.”

This is not the AI drawing blueprints. It is the AI refusing to let vague blueprints reach the factory floor.

The constraint moved upstream

Steve Yegge’s Gas Town orchestrates dozens of agents simultaneously. His observation: when the factory runs fast, humans must invest substantially more effort in architectural decisions, feature prioritization, and specification clarity. The constraint moved upstream. The tooling did not follow.

Anthropic’s official guidance is to find “the simplest solution possible, and only increase complexity when needed.” For most applications, a single agent is enough. The bottleneck is not the factory. The bottleneck is knowing what to build.

Each additional agent multiplies the opportunities for blueprint errors to propagate. If your specifications are ambiguous, one agent might misinterpret them. Twenty agents will misinterpret them in twenty different ways.

This is the same dynamic that kills AI pilots. The factory works. The design department does not keep pace.

What I am still figuring out

The Socratic design department is conceptually clean but I have not seen it built. The closest examples are design docs reviewed by senior engineers, but that is expensive human time, not tooling. There may be a reason nobody has built this. Blueprints are contextual in ways that resist automation.

The 66% multi-agent adoption stat comes from enterprise surveys. I suspect it is inflated. If routing between specialized prompts counts as “multi-agent,” the number is meaningless. If it means genuine autonomous coordination, 66% seems implausibly high.

Huntley’s results are striking but specific to his context. He has years of experience tuning these loops. The technique may not transfer to teams without that foundation, which brings us back to the tooling gap. If the skill is rare and hard to teach, the tool matters even more.

Cursor’s fix was not a better factory. It was less factory. The integrator role they added “created more bottlenecks than it solved.”

The lesson is not about factory architecture. It is about where to invest. The industry has invested in orchestration. The constraint is specification. Evals alone will not save you. You cannot evaluate your way out of building the wrong thing.

Build the design department. The blueprints matter more than the factory.